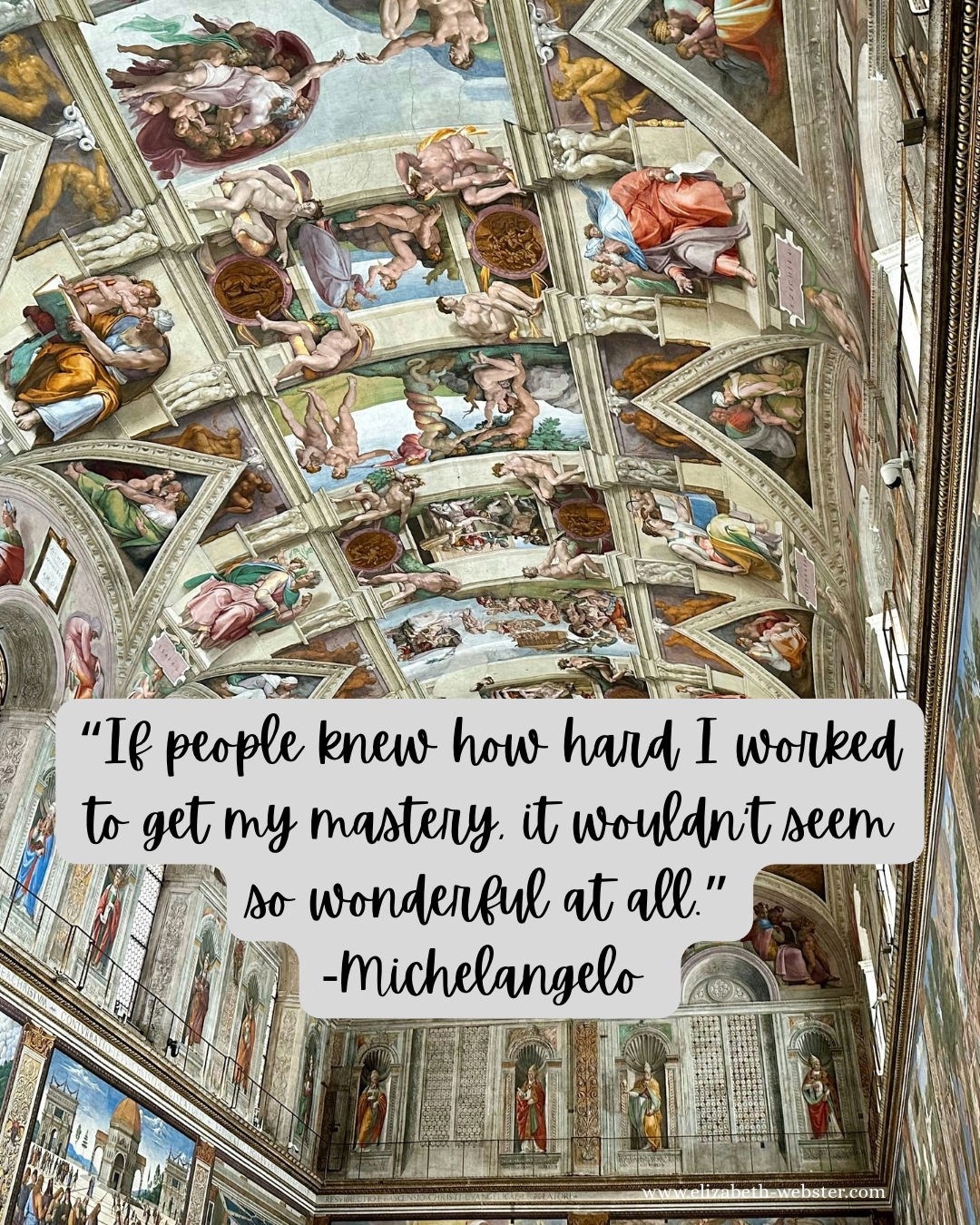

A Lesson in Making: Michelangelo’s Micro Masterpiece

Exciting news resounds from the art world, as experts at Christie’s believe they have verified the authenticity of a Michelangelo sketch. The small red chalk drawing of a foot will go to auction in February. Experts believe the sketch served as the basis for the figure of a priestess, Libyan Sibyl, that Michelangelo painted on the east end of the Sistine Chapel.

While Michelangelo’s sketches offer a first glimpse of his masterful techniques and the incomparable artwork that would follow, they also contain glimpses of the artist’s insecurity. Moreover, Michelangelo’s later effort to have them destroyed holds timeless lessons for creatives.

Within the fervor surrounding one small sketch is a big question: why does a rough sketch matter?

The sketch’s winding journey from discovery to verification presents with the momentum of any great detective story. An anonymous seller in California explained to experts that he had inherited the drawing from his grandmother in 2002, though it had been in his family since the 1700s. Experts quickly went to work, conducting a thorough analysis like a plot line.

The paper itself shares attributes of other 16th century papers. The drawing’s combination of red chalk on the front (recto) and black chalk on the back (verso) is consistent with Michelangelo’s other studies of Libyan Sibyl. The inscription on the sketch, “Michelangelo Bona Roti,” was likely written by an anonymous 16th century owner. This same inscription appears in many of Michelangelo’s sketches.

The evidence is staggering, but another aspect of the sketch’s backstory gave me pause. Sketches like this matter so much because they’re so rare. Though Michelangelo allegedly made thousands of similar sketches in his lifetime, he burned most of them before he died. In 1518, Michelangelo instructed his assistant to destroy many of the drawings he relied upon to create the Sistine Chapel.

Why?

Giorgio Vasari wrote in The Lives of the Artists in 1550 that Michaelangelo didn’t want to reveal his rough sketches, “in order that no one should perceive his labors and tentative efforts, that he might not appear less than perfect.” Michelangelo wanted us to see his finished product, rather than his process.

As a writer, I understand the freedom baked into a first draft. Its hidden quality, the certainty I have that no eyes will ever see it, gives me license to experiment and to play. Alone in the studio with his model, Michelangelo also likely relished the freedom not only to plan but to dream. Think of how much less pressure he felt enclosed in his own four walls. Michelangelo famously said, “I cannot live under pressures from patrons, let alone paint.”

Despite recognizing that Michelangelo felt self-conscious about his sketches, Vasari saw his genius the way we do. When describing Michelangelo’s Pietà, Vasari wrote: “It is certainly a miracle that a formless block of stone could ever have been reduced to a perfection that nature is scarcely able to create in the flesh.” On Michelangelo’s David, Vasari wrote: “The grace of this figure and the serenity of its pose have never been surpassed … anyone who has seen Michelangelo’s David has no need to see anything else by any other sculptor, living or dead.” Vasari believed Michelangelo to be the greatest artist of all time.

Michelangelo was clearly divinely inspired. Many of his quotes reference his belief that his art and God are intertwined: “Every beauty which is seen here by persons of perception resembles more than anything else that celestial source from which we all are come.”

Yet while his art reveals his genius, his dogged process shows his humanity.

His life as an artist was laborious. Michelangelo was interested in anatomy and performed dissections. Of course, he relied on live models as well. He sketched from death as much as he did from life. When it came time to realize his sketches in another medium, Michelangelo never ducked hard work. Painting the Sistine Chapel took Michelangelo four years to complete. He painted the demanding, layered frescos while standing on scaffolding, his brush held high above his head.

Vasari wrote about Michelangelo’s efforts with the same wonder that he described the artist’s genius. Vasari reported Michelangelo was often so spent from painting he slept in his clothes. He didn’t sleep well. He even created a cap with a candle, a contraption which allowed him to optimize his insomnia and paint in the middle of the night.

He was an artist blessed with unfathomable, otherworldly skill. But he wasn’t only that. Michelangelo was also a person who possessed the discipline to execute it.

Maybe I’ve been approaching first drafts all wrong. These initial attempts - our brainstorming sessions, our rough sketches, our wobbly molds - aren’t only valuable because they’re so hidden they free us. They also matter because they’re the first sign of commitment. They’re the transition point from idea to expression. It’s as though we’re on the other end of a promise, ready to acquiesce to an unknowable journey. They’re the clumsy, human part of creativity. And they’re beautiful for their imperfections.

Later, when creatives comb over their first efforts like they’re panning for gold, they discover nuggets of their own genius. Slivers of creativity made manifest. Gems that fill creatives with inspiration that is equal parts practical (I think I can use this …), momentum-building (I’m ready to get back to work now), and imbued with awe (How did this come from me?).

For his part, Vasari tellingly kept Michelangelo’s sketches like small treasures. Because he saw them for the scraps of genius that they were.

“Of such I have some by his hand, found in Florence, and placed in my book of drawings. From these, although the greatness of that brain is seen in them ….”

Perhaps we should follow Vasari’s lead and hold tight to the messy evidence of our first try. Who knows? We may come to treasure it later.